To paraphrase A. A. Milne, creator of Winnie the Pooh—and Tigger too!—the things that make us different are the very things that make us us.

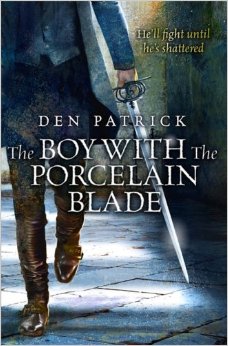

But when you’re different—and who isn’t?—fitting in is a difficult thing. It’s far harder, however, for the likes of Lucien de Fontein, a young man who has no ears, I fear, and must display his most significant difference every day, come what may.

There are others like Lucien. Other Orfano, which is to say “witchlings […] whose deformities were an open secret among the subjects of Demesne in spite of the Orfano’s attempts to appear normal.”

Lucien has long hair to hide the gory holes on his head, but no matter how hard he tries to fit in with his fellows, they reject him repeatedly. Evidently, “the life of an Orfano was a lonely one,” if not without its privileges:

Years of schooling. Almost daily education in blade and biology, Classics and chemistry, philosophy and physics, art, and very rarely, assassination. He had been given the best of everything in Demesne as set down by the King’s edict, even when he’d not wanted it, which had been often. Now he would be bereft of everything; all thanks to Giancarlo.

Giancarlo is Lucien’s Superiore, an instructor of sorts who can’t stand the sight of our Orfano… who has gone out of his way to break him at every stage. So far, Lucien has held fast in the face of Giancarlo’s cruelty, but everything comes to a head during his final Testing: the emboldening moment when he is to trade his paltry porcelain blade for real steel, and indeed the scene with which Den Patrick’s debut begins. But the bastard master pushes his intemperate apprentice too far, and Lucien’s response—to attack Giancarlo rather than the innocent he is to kill—leads to his exile from Demesne.

This isn’t punishment enough for Giancarlo, apparently. Slighted by his student, he dispatches several soldiers to slay Lucien before he can even leave. Luckily, the boy with the porcelain blade escapes, aided by sweet young Dino and their determined teacher.

Too soon, Lucien’s luck takes a turn for the worse. “As an Orfano he was immediately recognisable. Anonymity was the province of other people,” so when he is waylaid and warned about the wicked sins committed in the city—in the name of the King, no less—he realises that for Landfall to go forward, he himself must go back. And in the process, perhaps he can save the damsel in distress he had abandoned.

To Patrick’s credit, Rafaela is only ever a damsel in Lucien’s imagination, and though she is occasionally in distress over the course of The Boy with the Porcelain Blade, so too is our intermittently hapless protagonist. Both characters are well handled on the whole: lonely Lucien is engaging when he’s not being an absolute brat, and I was immensely impressed by the author’s predominant depiction of Rafaela as intelligent and assertive rather than frivolous and submissive, as love interests often are in fantastic fiction.

The supporting characters hardly get a look-in, however, and though there’s the potential for the other Orfano to be better developed at a later date—The Boy with the Porcelain Blade is but book one of The Erebus Sequence’s three—I was disappointed by the author’s treatment of Dino and Anea especially.

Truth be told, this isn’t a book you should come to for the characters. Nor is its anaemic narrative particularly remarkable: off the bat, the plot is paltry, hard to get a handle on, and the frequent flashbacks Patrick treats us to disrupt the pace on a regular basis. That said, the second half is substantially more satisfying than the first plodding part… so there’s that.

The best thing about The Boy with the Porcelain Blade is certainly its setting. The author doesn’t waste his time (or ours) describing the whole wide world—just a small space therein. This narrow focus does detract from the scope of the story, but it also allows the author to really zero in on what makes Demesne special… much the same state of greatness in decay that made Gormenghast memorable:

Demesne. His home. A landscape of rooftops and towers […] crumbling masonry and dirty windows. Out of sight were courtyards and rose gardens, fountains clogged with leaf mould, statues embraced by ivy. Forgotten cloisters linked old rooms carpeted only in dust. Bedrooms beyond counting, pantries and kitchens. And somewhere within the castle were the four great halls of the four great Houses, each vying with each other for decor and taste. At the heart of it all was the circular Keep of the King, their mysterious benefactor, saviour of their souls.

If he even existed.

Overall, I enjoyed The Boy with the Porcelain Blade—enough, at least, that I’ll read the sequel, for the time being entitled The Boy Who Wept Blood. But I did not adore this debut. Though it gets better as it goes, the first half of the whole is dull and clunky; the sense of humour that made the author’s barbed War-Fighting Manuals so marvelous is sadly absent; meanwhile what we see of the setting is excellent, but it needs to be bigger to sustain a trilogy. Would that there had been a better sense of that here at the start of Patrick’s larger narrative.

The Boy with the Porcelain Blade is pop fantasy, frankly, and by that measure, I imagine it’ll chart. As yet, it’s no number one… but maybe that’s to come.

The Boy with the Porcelain Blade is available March 20th from Gollancz.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He’s been known to tweet, twoo.